How to tell what to do next when you have no idea what to do next

A repeatable process for aligning your interests, focusing your effort, and making real progress without guessing.

Hi,

Completing an Eisenhower Matrix helps you understand what you’re already doing and where your effort is producing results.

But even after that exercise, it’s hard to know what to do next.

Without direction, most people choose their next goal because it sounds impressive, urgent, or externally legible. That usually makes things worse, because it introduces a direction that doesn’t fit how they’re wired or what they actually want to spend time doing.

There’s a better way to find clarity. Before explaining it to you, though, I need to tell you a little bit about the physics of dominos.

A standard domino is about two inches tall. On its own, it doesn’t look powerful, but when dominos are sequenced correctly, even a small one can knock over something much larger.

When a domino falls, it releases stored potential energy. That energy is enough to knock over another domino about 1.5x larger. That larger domino has more potential energy, which allows it to knock over something bigger still.

Repeated over time, that scaling compounds. A chain of small dominos can eventually knock over something dozens or even hundreds of times larger than the first one.

This only works because each domino is sized correctly to knock down the very next one. If you try to skip ahead or fell something too large too early, nothing moves. When each step is the right size, momentum builds naturally.

That’s how goals work, too, and that’s the logic the process we’re about to talk about is borrowing. When people get stuck, it’s rarely because they’re lazy or unfocused. It’s because they’re doing too many things that don’t amplify each other or lead anywhere.

Gary Keller and Jay Papasan wrote an amazing book called The One Thing. In it, they talk about the benefits of finding the one, single thing which could change your life forever, The Big Domino, and putting an inordinate about of time and effort into tipping it over. In order for the domino to tip, there are all sorts of smaller things that need to fall into place, but your mind should be laser-focused on The Big Domino, and make sure 85% of your effort is focused into pushing it over.

You probably can’t become president tomorrow. But there are concrete outcomes between here and there that are knowable, even if you can’t see them yet.

Progress usually comes from identifying one outcome that, if it occurred, would make many other things easier or unnecessary. That’s your Big Domino. It’s the next meaningful result that would change your situation. Once it falls, it gives you the leverage to go after the next one.

For example, “speaking at a conference” isn’t a singular event. It’s the result of a hundred little things that happened to get you there. The more of those actions that align together, the more quickly you can move and the fewer steps it takes to achieve.

A clarifying question I really like asking is “What can you do in the next 12 months that would revolutionize your life and make sure you were never the same person again?”

The answer to that question is the seed of your Big Domino. However, it needs to be an actual event, like finishing 12 books in one year, or something else which you can feel, not an idea or concept which is not tangible. We call those SMART goals.

A SMART goal is a type of goal that follows five specific criteria to ensure that it’s clear and reachable. The acronym SMART stands for:

Specific: The goal should be clear and specific, so anyone who reads it can understand what is meant.

Measurable: The goal should have criteria for measuring progress and success. This means you should be able to track and quantify your progress.

Achievable: The goal should be realistic and attainable, meaning it is something you can actually accomplish with the resources and time you have.

Relevant: The goal should matter to you and align with other relevant objectives. It should make sense within the broader context of your bigger plans.

Time-bound: The goal should have a deadline or time frame, so there is a target date to focus on and a timeframe to work toward.

For example, instead of saying “I want to get fit,” a SMART goal would be something like: “I will jog for 30 minutes three times a week for the next three months to improve my cardiovascular health and be able to run a 5K by the end of that period.” This way, it’s specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

Having a single SMART goal you are working toward gives you focus and direction.

Most people don’t fail because they can’t work hard. They fail because their effort is spread across dozens of disconnected activities, none of which are strong enough to knock over a real domino.

That’s what the rest of this process helps to clarify.

Once you identify that domino, it’s about completing all the tasks required to knock it over. If it does, great. You’ve moved forward, and a new domino will be standing in front of you.

If it doesn’t, that tells you something important is missing, and you can only discover that by trying.

Either way, this is how you decide what to do next, and how to line up your dominos so they knock down bigger and bigger goals for you in perpetuity.

Step 1: List Your Interests

First, we brainstorm. With this exercise, you’re trying to surface the things that already have energy, not things you think you should want.

Open a blank page and write down:

Work you find yourself thinking about when you’re not “supposed” to be thinking about work

Skills you keep returning to even when no one is asking you to

Problems you enjoy wrestling with, even when they’re annoying

Improvements you keep wanting to make to things you already do

Activities that feel absorbing rather than effortful

A useful test is to ask “If no one would ever see the output, would I still want to work on this?”

If the answer is no, it doesn’t belong here.

Stop when the list starts repeating itself or circling the same themes. That repetition is already a clue.

By the end, it should look something like this:

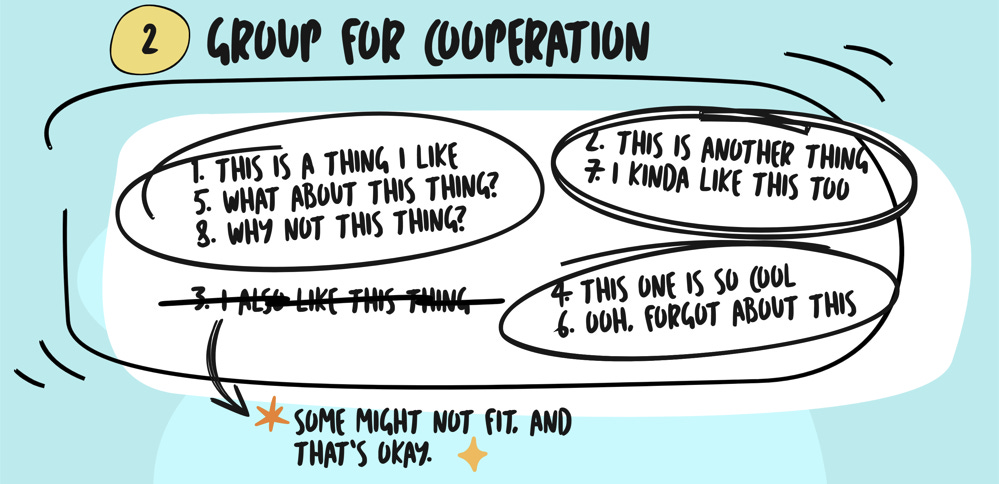

Step 2: Group For Cooperation

Now you’re going to take that list from Step 1 and start grouping them.

Ideally, what you’re doing here is aligning which interests could realistically work together if you pursued them at the same time.

Progress in one should make progress in the others easier, not harder. For example, these might belong together:

Researching a topic

Writing about it on your blog

Talking about it on podcasts

Getting an article published

Those are very different activities, but they cooperate. Each one produces inputs for the others. These usually don’t belong together:

Learning an entirely new skill from scratch

Maintaining a high-output content schedule

Building a complex system you don’t understand yet

Each of those has a bunch of tasks under it, and we’re trying to isolate the base tasks that need to happen before you unlock the next step.

As you do this, expect friction. You’ll move items around. You’ll realize some things only seemed related until you put them next to each other. You’ll probably notice that one or two items don’t fit anywhere yet. That’s fine. Leave them out for now.

A few important constraints:

You want multiple buckets, not one

Aim for 3–5 buckets, not 10

Buckets can be uneven

Buckets are provisional

Don’t label the buckets

Make sure to check in with your body as you do this.

When a grouping is wrong, it usually feels tight, heavy, or forced. When a grouping is right, there’s a sense of ease. Things click, and you don’t have to argue yourself into it.

If something feels off, don’t rationalize it. Adjust the buckets until the system feels coherent

Once you have buckets that cooperate instead of compete, you’re ready for the next step.

By the end it could should look like this:

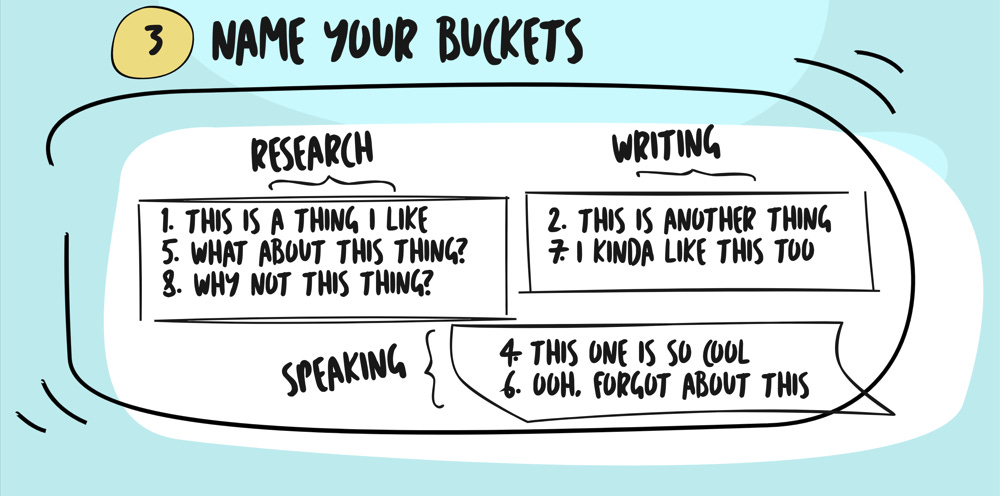

Step 3: Name Your Buckets

Up to now, you have a list of live interests grouped into buckets that can work together.

Those buckets are still unnamed because naming them too early makes it harder to see connections easily.

Now that everything is in buckets, it’s time to name them. Concentrate on what kind of work is being done in the broadest, most obvious sense.

Think:

What lane is this?

What mode of work is this?

If someone looked at this bucket from far away, what would they say I’m doing?

For each bucket, write a simple noun phrase that describes the kind of work inside it.

If you can’t label a bucket cleanly, it’s probably doing too many things or it shouldn’t exist yet.

Fix the bucket, then label it.

When you’re done, you should be able to say “Okay. These are the kinds of work I’m actually interested in doing right now.”

By the end it might look like:

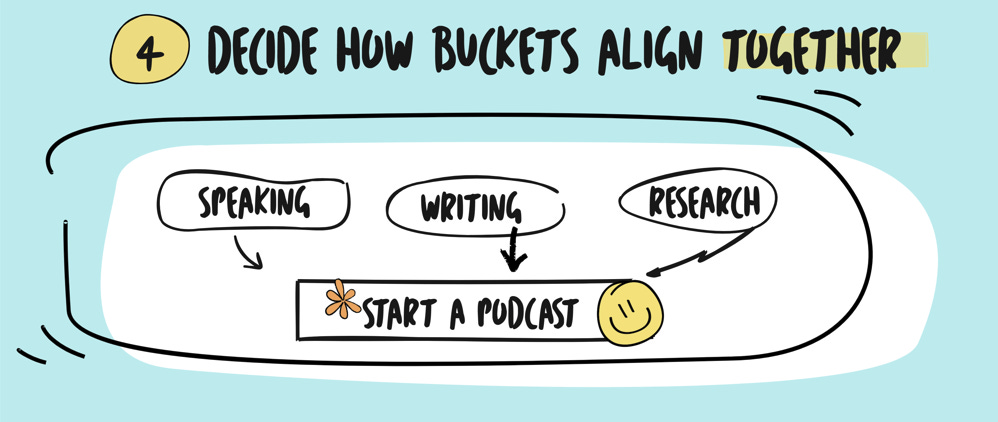

Step 4: Decide Which Buckets Align Together

At this point, you have 3-5 overarching buckets, labeled simply and clearly. Now it’s time to group those buckets and decide which belong together.

You’re not necessarily trying to make all of them fit, though it would be great if they did. You’re seeing which ones naturally cluster.

Some buckets will clearly support each other.

Some will feel neutral.

Some will feel like they belong to a different phase entirely.

Cluster the buckets that feel like they could amplify your effort if they were done in tandem. Now look at that circled group and ask “If I kept doing these together, what would they lead to?”

Don’t overthink the answer. Write the first plain, obvious thing that comes to mind. This is your next Big Domino.

If you see nothing that aligns, go back and adjust until something points.

This step ends when you can say “These buckets go together, and this is what they’re moving me toward.”

The result could look look like this:

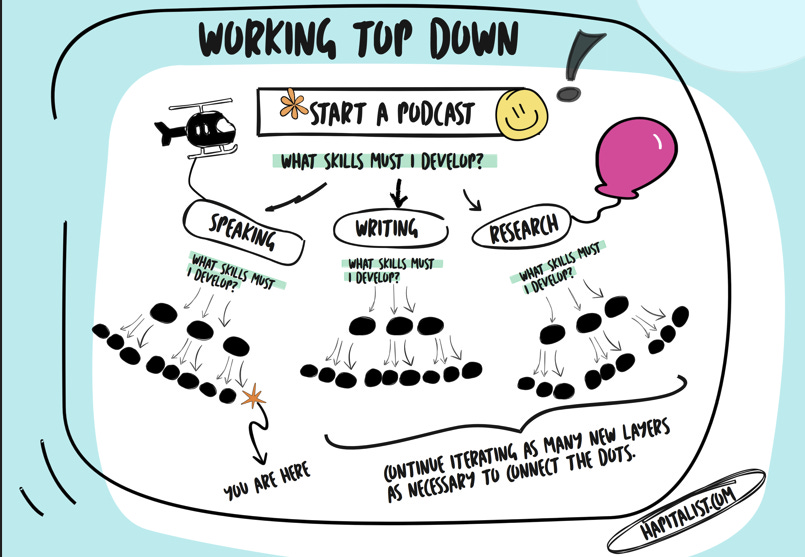

Working From the Top Down

So far, we’ve talked about working bottom up by starting with what interests you, grouping it into buckets, seeing what aligns, and letting the next domino emerge from the work itself.

But you can also run this process from the top down. Sometimes you don’t feel lost. Instead, you feel pulled toward something specific. In that instance, you might have a clear outcome in mind:

You want to speak at conferences

You want to be known for a particular idea

You want to move into a different room or role

You want to build toward a bigger, longer-term identity

That outcome might feel far away, but it’s still useful. In this case, the Big Domino is already visible at the top of the pyramid.

When you work top down, the question changes.

Instead of asking “What do my interests point toward?” you ask “What would have to be true for this outcome to be possible?”

Then, you work backward.

What kinds of work would support that result?

What buckets would need to exist beneath it?

What actions would need to happen consistently for this domino to even have a chance of falling?

You don’t need to map the whole pyramid. You only need to identify the next layer down that directly beneath the one you can already see.

Once you do that, the process becomes the same. You:

Identify the buckets of work that could support that outcome

Check whether those buckets cooperate or compete

Adjust until they make sense together

Do the work long enough to see what happens

If the domino falls, great. You move closer to the top. If it doesn’t, you’ve learned there’s a missing prerequisite you couldn’t see from above.

This process works in either direction, and most of the time, you’ll be doing both at once, both using what you want to guide your effort and using what you learn to reshape what you want.

After you’re done, it might look like this:

Putting It Together

This process is infinitely repeatable. Every time you get stuck, come back to it, stacking dominos over time to create an unending pyramid of skills and talents, each pushing you upward toward the next Big Domino.

What you’ve done up to this point is identify one coherent cluster of actions that seem to work together and that you believe lead to a specific result. You won’t know for sure until you test it in the real world.

When buckets truly aligns, they should point in one plausible direction. Once they do, you do the work to execute the tasks in those buckets, trying to knock over that domino.

If you reach your goal, you’ve confirmed that:

Those buckets actually belong together

That direction is viable at this level

You now have one more solid piece of your career structure in place. If it doesn’t work given your assumptions, that tells you there’s something missing you couldn’t have known without trying.

Go back and update your assumptions. What might you have missed? Usually, it’s one of a few things:

A skill you don’t have yet

A signal you’re not sending clearly

Access to people or rooms you’re not in yet

A prerequisite step you didn’t know existed

These are unknown unknowns, and everyone faces them. Don’t beat yourself up if you run up against them. You can’t plan for things you can’t see in advance. The only way they surface is by trying to knock the domino over and seeing where the system breaks.

However, while you can’t plan for something you can’t see, you can plan to find something unexpected, and give yourself enough time to process what you find thoroughly. If you give yourself enough time and resources to deal with these challenges, they can even be fun, at least as thought experiments.

If you’re constantly running at the edge of your resources, though, then it could be catastrophic. So, build enough contingency into everything you do, and be generous with yourself.

When you reach one of these blocks, don’t get discouraged. Go back to your domino and update your assumptions to add what was missing into the system. Regroup with your buckets with better information and see if there’s anything already in your skillset that can help you overlooked earlier.

Once you’re confident in your new direction, run the same process again.

That’s how progress actually works.

You’re not supposed to know everything up front. You’re supposed to build forward until reality shows you what’s required next, and then respond.

This process gives you a way to do that, one domino at a time.

Each of those dominos above were once their own Big Domino with their own actions that supported toppling them. Now, they might seem “easy” and “quaint”, but just remember that everything you’ve done up to this point supports the next thing you will do. The more those things align in a singular direction, the bettwe.

That said, do you notice here that as the dominos get bigger and bigger, you need more and more areas to support it? Including ones that could seem unrelated?

The last thing I want to leave you with is that often, seemingly unrelated ideas and modalities are necessary to topple your biggest goals. If you want to be the CEO of a big company, then you need to understand both human relations and finance, along with a dozen modalities that don’t easily align together…

…or at least they don’t seem like they relate at first.

If you feel that kind of anxiety in your own career, this exercise is even more important. If you can lay this all out, and realize that your disparate actions are driving toward the same goal, it’s easier to commit to them.

Who knows? You might even have to go back and learn something completely new from scratch to build up to the level where you can push something bigger over.

This doesn’t mean to be chaos. However, it also doesn’t not mean that chaosing for a while could be exactly what you need, especially when you’re stuck.

The problem with chaosing usually comes with dabbling in one thing or another without every focusing enough to push over that domino and master that task. If you get pulled in a direction that seemed wholly afield, perhaps it’s your intuition knowing more than you, and you will need it later…

…but if you’re gonna make a pivot, make a hard pivot. Do the thing enough to really learn it. Otherwise, you’ll end up with a bunch of listless effort that doesn’t get you anywhere.